All this talk of book banning made me think it was time to repost a piece from a few years back…

Going to the library was something offered as a reward when I was growing up. The prospect would be dangled in front of my sister and me like a carrot: behave like respectable adults while braving whatever crucible we’d been asked to endure – trip to the dentist, barber, or lunch at some cranky relative’s, and we could very well be gifted with the chance to sit on the floor pawing through stacks of whatever we wanted.

At the public library in Brewton, where I spent the first ten years of my life, that also meant a trip upstairs. There wasn’t anything of interest to anyone else up there – periodicals, marginal art – still, it was UPSTAIRS. A place neither my mother nor sister had any interest in visiting. I would look out over the banister at what seemed to be endless aisles of stories unfolding from Dixie to Cairo. I’d perch next to the big potted palm at the top of the staircase, scouring whatever I’d yanked from the shelves until I was told I had to make a choice and come back down to my family’s reasonable facsimile of reality.

I’d always read above my level, which is not to say I was any smarter than anyone else – well, perhaps as far as reading went I was. Alvoy would always let me check out whatever I pleased. “If he’s old enough to ask for it, he’s old enough to read it,” she’d say. I think she was thankful for anything that would keep me out of the reptile-infested creeks snaking in and out of our neighborhood.

In those pre-Google days, it was too time consuming to look up every word I didn’t know in a dictionary – if there was someone within hollering distance who could clear things up, they were fair game. “If you ask me what ONE more word means, I’m gonna tear that book into a million pieces and flush it down the toilet, and you know I’ll do it!” my sister hissed, locking the bedroom door behind her.

One 4th of July at the beach, I saw Alvoy reading Ira Levin’s Rosemary’s Baby. Al never cared for scary books – or movies, so this was unusual. I can still remember the design on the hardcover – blood red letters over a gargoyle-infested New York City apartment building. As my sister and I attempted to lure her into the water to play, she ignored us. Turning another page, her eyes, still too young for bifocals, squinted in the afternoon sun. “I won’t sleep for the rest of my life, but I have to finish it.” A few days later I spied the book on the entrance table – a sign it was finally done and on its way back to the library. Alvoy eyeballed me over a dust cloth. “Can—” was all I could get out. “Only if you promise not to follow me around the house like a hound,” she said, firing up the big Electrolux. “I don’t know what every word in the universe means. And if you’re too scared to sleep, don’t holler for me.”

A couple years later when we moved to Clarke County, I’d peruse the new paperbacks underneath my Grandma Bess’s reading chair. Her son’s mother-in-law, a woman of questionable artistic taste, would drop off a new box of cast-offs every couple of months – Tropic of Cancer, The Exorcist, Jaws. I’d sprawl underneath the chair, devouring whatever was on the pile as the adults talked politics and religion, too busy dunking their pound cake in sugared-down coffee to notice me wallowing in the literary mire below them. A minister’s widow, Grandma Bess would feign ignorance if I held up one of the books in question – “You don’t need to read that, it’s about the devil – or hippies, I forget which.”

I continued my quest for forbidden intellectual property when I discovered that, behind the librarian’s desk in the private school I attended, there were two whole shelves of books unavailable for check-out. Deliverance, Helter Skelter, Leaves of Grass. I had no idea what they were, but I wanted at them. “You need a parent’s note to check those out,” Mrs. Matthews, the librarian, whispered. She said it like nobody’s parent had sent a note – ever. “Now go back to your study table with the others.” Was it as simple as that? All this contraband for the taking? Who was bringing in all these titillating titles? And why, in the seat of the Bible Belt, was anyone allowed to take them out with a parent’s note in the first place – even if the parents willing to do it didn’t exist? It was no surprise I found I was the only kid who had a parent agree to sign off on it. A few days later, my mother bent over the couch, scanning my paperback copy of Story of O. “What’s that one about?” Alvoy asked. “I’m not sure yet,” I said, ten chapters in. And that was the truth.

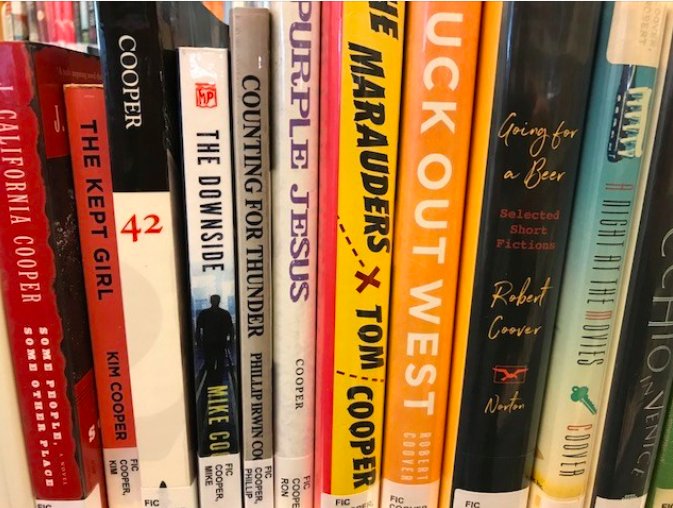

I’d had someone email me recently to say they’d found two copies of Counting For Thunder in a small-town library in Colorado. Another even spied one at a library in Sydney. Days later when a friend texted to say they’d seen my book on the shelves here in the Santa Monica Public Library, my adopted hometown, I was on my way to a meeting. It barely registered. A couple days later, I found myself walking a block away from the library with time to kill. Eons ago when Counting For Thunder began as a one-man-show, one of the last scenes actually took place in the basement of the Santa Monica Public Library. It was a thing far too complicated and emotional for me to find a way to include in the book or the movie. As I slung the backpack over my shoulder and headed down the ramp into the building that takes up most of a city block, I felt more than a bit like you do when you’re about to make love to someone you fancy for the first time. My hands trembled. My throat dried up. My heart began to race. I wasn’t prepared for such. I made my way past the A’s and B’s and finally to the aisle that boasted Ca-Co on the side of its shelf. I walked past the librarian who was restocking something about dragons. Kneeling down, I ran my hand over the binding – “Cooper, Phillip.” I pulled the book out. “Santa Monica Public Library” stamped across the top. The book next to mine, also by someone named Cooper, was called Purple Jesus. I wondered what it could possibly be about without taking it off the shelf. One of the many homeless who hang about the library asked one of the librarian ladies behind me – “Do you have anything on brisket?” “Fiction or nonfiction?” I heard the librarian lady ask.

Although it’s doubtful I’d find a copy of Counting For Thunder in any of the small-town libraries I grew up in, I hold out some small hope that somewhere on the Redneck Riviera, some kid is stumbling across a shelf available only to those with parents reckless enough to say he or she can read anything on it. A parent who’ll simply say, “If you’re old enough to ask for it, you’re old enough to read it.”